Early-warning weather systems saving lives and expanding livelihoods

The following two projects, funded by IDB together with NDF, show how early warning systems are helping small farmers in Latin America prepare and adapt to volatile and extreme weather patterns related to climate change, with far-reaching results

1. Proadapt Gran Chaco (Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia)

The hot, semi-arid area of Gran Chaco, which spans Paraguay, Argentina and Bolivia and the Brazilian Mato Grosso, has been described as one of the most isolated places on earth.

“The farms themselves are spread very far apart,” recalls Carmen Lacambra, Director of Research and Environmental Services at Grupo Laera, who visited the area as an evaluator. “Some farmers might have 200 hectares of land for running less than 40 cows.”

Farmers in the region experience unpredictable rainfall, characterised by severe flooding, which threatens crops, livestock and even human lives.

“Small areas can experience large amounts of rain, sometimes in a very short time," says Proadapt Project Coordinator, Mauricio Moresco. "And our meteorological stations, separated by vast distances, can’t capture all of the data in time for communities to prepare for the onset of floods."

Building an app

Working with peers from inside affected communities, Proadapt Gran Chaco set out to address this problem. The first step was to get shared access to meteorological information from more than 150 measurement stations across the three countries, while identifying the remote areas where locals would need to contribute by collecting rainfall data themselves.

As well as local radio, and cell phone communication including a WhatsApp group, the project has also developed its own specialised app managed by community leaders to alert farmers and their families of approaching weather hazards.

Originally the project was aiming for a very high-tech information platform, but they were held back by the fact that many farmers didn’t have access to running water or electricity, let alone phone or Internet connections. So instead the early warning system evolved into a more traditional approach using radio and some Internet services such as a WhatsApp group with 150 registered users as well as the app. When the farmers in the group visited settlement areas, they can get online and upload information to mobile devices.

Lifesaving results

“The App group did quite well,” says Lacambra. “During the 2018 rainy season, when it rained a lot and the waters rose, thanks to the early warning systems, the losses in terms of cattle as well as income was significantly reduced."

“And not a single life was lost,” Moresco stresses. Roads were reportedly submerged, scores of homes were toppled, or buried by heavy mudslides, but more than 10,000 people and half a million cattle were successfully evacuated.

An unpredictable river

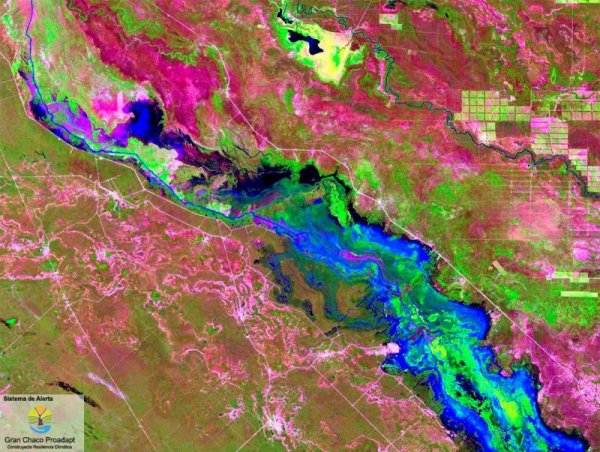

The Pilcomayo, which flows over more than 1,000 km of the region, and borders all three countries, is at the centre of these weather disasters. It’s a river that carries very high volumes of sediments in the order of 90 to 160 million tons per year, and is continually building its own riverbed, clogging itself, by dropping the sediments in its own bed, raising it again and again, to fill it. When this happens, the channel no longer has the capacity to transport incoming water and takes another course. ‘The river doesn't want to go that way anymore; now he wants to go there,’ is the anthropized way the locals describe the Pilcomayo.

Getting to know this river better was another major step in the project. “We did this by developing risk maps,” Moresco explains. “Using information from the communities as well as historical satellite imagery.” This was no easy task; the risk map of the lower river basin alone covers an area of approximately 50,000 square kilometres.

However, at the centre of this information gathering was anthropologist Luis Maria de la Cruz, who has spent his professional life on the Pilcomayo, living with indigenous communities and observing the river’s changing twists and turns.

“This is much more than just computer modelling,” Lacambra insists, “but the result of real knowledge from the field, particularly from Luis Maria, who knows the region, the communities living of it and affected by it, and has walked the Pilcomayo, he knows the river.”

More than just a disaster alert

The app has evolved into a knowledge sharing system that goes beyond just preparing for disaster.

"People are much more aware now of the need to adapt to climate change with new practices and tools for how to raise livestock and how to make the best use of water, and we’re using the app to share this knowledge," Moresco says.

“Proadapt Gran Chaco visualised the role of climate for a lot of people who weren’t previously thinking about climate in El Chaco,” Lacambra affirms. Describing it as the first project of its kind in this area to even talk about how climate viability impacts people, productivity and livelihoods.

Strength through local ownership

It began as an umbrella project focused on the weather and the river but along the way, it began to ask other questions like what else could we do instead of cattle, and so they brought in beekeeping and organic honey. Then the project reached cities, which didn’t have adaptation plans, and now nine cities already have plans. “It is strengthening resilience because it’s touching institutions, it’s touching sectors and it’s touching people on the ground.”

Lacambra can’t resist praising the strength of the project’s implementing staff. “These are not consultants who were parachuted in from somewhere else. These are organizations from three different countries working together and supporting each other. The people driving this project forward are Bolivian Argentinean and Paraguayan experts and professionals. Their work will continue because they have strong links to this land; several of them live on this land; and they love this land.”

2. Proadapt Nicaragua, Cocoa and Honey Producers

Imagine an app for farmers that not only gives up-to-date weather reports but also coaches them on the right actions, technologies and tools to respond.

In response to a growing number of extreme weather events, Proadapt Nicaragua has developed an early warning system that uses climate and weather analytics as well as agriculture related information like seeds, soil and technology to help cocoa and honey producers adapt to harsher climate conditions.

Advanced planning data

Project Coordinator, Moisés Obando López, who works for honey and cocoa processor and distributor Ingemann, explains how trainings and early warnings using new publicly available climate and weather data from national and international sources, give farmers a heads up particularly on sudden temperature swings, or heavy rainfall and winds. “Using advanced medium and long-term planning. We’re working together with our farmer suppliers to reduce the risk of crop damage and harvest disruption related to changing and volatile climate patterns.”

“The project has found the sweet spot of mixing climate and weather analytics with data related to plants, soil and agricultural production,” says Svante Persson, Senior Operations Specialist, IDB. "That means if you have a cocoa plant, knowing how is it affected by soil mix, fertilizer, and water, and knowing how you can change that with the right mix of climate and weather data.”

Heavy rains and high winds

Moises talks through some examples. If heavy rains are expected, cocoa farmers get detailed instructions on drainage. This could be anything from eliminating the possibility of water collecting in pools to where and how farmers can create channels to direct potential flood waters intelligently away from their crops.

Responding to incoming high winds or storms, cocoa producers have learnt for example how to identify vulnerable trees and protect them using makeshift wooden anchors. Beekeepers given advanced storm warnings can actually load up their hives onto a truck and take them to temporary shelters – Moises assures us that the bees are happy to go along with this.

Optimizing production

"Producing honey means protecting the bees,” says Maria Francesca Blandon, a beekeeper in the program. She and her husband have ten years’ experience, but three years ago the rains were so heavy they lost 10 hives, which was half of their hives for that year.

“In other years it was the drought that affected us,” Blandon lamented. “And as we Nicaraguans say, I almost hung up my gloves.”

But they persevered and now, as part of the Proadapt program, have access to advanced daily knowledge of when it’s going to rain and how much. This enables Blandon, and others like her, to take the right actions in time to avoid losing honey yield and earnings.

App is a two-way street

However, Moises is quick to clarify that the system is not only about sending information in one direction. The app has been set up as a two-way platform where farmers share peer-to-peer information of their own. Some act as observer producers with weather stations on their farms monitoring temperature, humidity and rainfall levels. Others feed data into the system related to severe weather impact. This might be cocoa farmers assessing crop damage or changes in plant growth patterns; or honey producers sharing bee population data or changes in queen bee behaviour.

Going certified organic

At least 800 farmers are now active in certified organic programs. Success factors like the organic certification are win-win for the primary growers and for Ingemann, which is not a grower but involved in all other aspects of the production and processing.

“We need the ongoing guarantee of high-quality raw materials to feed into our supply chain," Moises confirms, “so continuing this cooperation even after the program closes, makes good sense for us and the farmers.”

While being distinctly different in technological and geographical terms the early warning systems in both the Gran Chaco and Nicaragua programs have gone beyond just salvaging livelihoods to actually expanding and enriching them.

Lacambra who knows both projects well, points out that the area covered by Gran Chaco was much more vast and challenging than Nicaragua from an isolation and communications standpoint, and the value chain much less established.

“Producers in Gran Chaco don’t yet have good market access even though they’re creating high quality products,” Lacambra concludes, adding that “the project’s established network across the region can be seen as a requisite step towards bridging this supply-chain gap.”

Persson sums things up: “The challenge of both the Gran Chaco and the Nicaragua projects was how to get information using the technologies available, out to the right people in the language they understand, and in a way that they can relate to and act on. Clearly both projects rose to meet this challenge, with credible results.”

The article is the second in a series introducing Proadapt, a regional initiative funded by IDB in partnership with NDF, to build climate resilience in micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises in Latin America and the Caribbean.

More information:

Pescadora climate resilience program finds plenty more fish in the sea